Oak and Home Winemaking

Written By: Michael Williamson

Creation Date: Monday February 15th 2010

Last Updated: Thursday August 29th 2019

1. Introduction.

Oak has a place in almost every winemaker’s process, but the timing of use, type, size or quantity of oak and extent of use will vary depending on the type of grapes, style of wine desired, the scale of wine production, as well as the philosophy of the winemaker.

The use of oak can vary between the following styles that you may be interested in:

- Fresh, light, ready-drinking wine

- Refined, aged wine of a particular style

- Fruit driven, intensely flavoured wine

- Experimental or unusual styles

- Unusual (or less common) grape varieties

- And of course whether the wine is made from grapes or other material, eg country wines.

Oak flavour traditionally was imparted to wine only by use of oak vessels, eg barrels, that at its best transferred pleasant wood aroma and flavour to the wine. as well as softening some of the harsh flavours, for example from excessive skin or stalk contact.

Small amounts of oxygen enter the wine through the oak of a barrel soften tannins and add complexity. Also the water in wine slowly evaporates though the oak, increasing the concentration of alcohol, flavour and aroma compounds.

Direct contact of the wine with “raw” un-toasted wood would introduce aggressive undesirable wood flavours; therefore most oak in contact with wine is toasted to a light, medium or heavy toast. (A heavier toast with charring also exists which is not generally used with wine, but with specialised spirits).

The heavier the toast, the less aggressive woodiness, but a different spectrum of flavours emerge.

2. In Practice

Like most home-winemakers at some stage I want to create the harmonious combination of wine with oak. Where do I start?

If I am making 200 to 300 litres of wine then a barrel might be just what I need, but what if I am making a small quantity in a 5 litre flask? Or what if I plan to use a stainless steel tank, plastic drum or glass demijohns I already have?

Let me return to these issues again below after discussing the use of barrels in the home winery.

3. What Type of Barrel?

Whilst I might aspire to buying a new French or American Oak barrel at some stage in the future, both the cost and the overpowering intensity of the wood flavour imparted to the wine make this almost totally impractical for the home winery. A much more feasible alternative is a used barrel that has seen two or three vintages in a commercial winery and is sold at a fraction of the cost either directly from the winery, through a local cooperage or from a winemaking equipment supplier. Even better if the barrel has been re-shaved on the inside (several millimetres of wine-affected wood removed to expose clean oak) and toasted.

If you are uncertain of what type of oak to use I would recommend starting with French oak, medium toast which I think is the most versatile.

If I am making a white wine in a wooded style I need to use a barrel that has only ever been used for white wine. Even if a red wine barrel is re-shaved it can never again be used for white wine. If I want to keep my options open I can buy a barrel previously used for white wine, which I can then use for either red or white wine.

4. Buying

Before buying a second hand barrel I ask if I can smell the barrel. This may offend the person selling it to me, but I need to check if there is any hint of vinegary or mouldy smells particularly, or any other "off" odours that might suggest bacteria or contaminants that may spoil the wine. There's no alternative but to reject them.

5. Locating and Positioning Safely

You need to plan where you are going to keep your barrel during maturation – a place in the cellar that is not right in the way of all the other activities you need to do with your other wines and support it on a cradle which bears the weight on or near the hoops . I use two parallel beams 700x100x100mm held together on two "feet" 700x135x45mm. Together these four pieces of timber make a 700x700mm cradle – one for each barrel I am using.

Safety is a consideration as you do not want 200kg or more of a full barrel to roll off the cradle you are using.

I also use four wedges made from 100x100mm timber cut at 30 degrees to hold the barrel safely on the beam. Once in position I drill over sized holes through the wedges into the beam and loosely slip in large galvanised nails to hold the wedges, but also enabling them to be easily removed at any stage.

If you plan to fill and empty using a siphon you will want to plan to keep your barrel elevated above the height of any bucket you are planning to use. This is unnecessary if you use a wine pump. Further height can be gained by brick pillars made of alternating pairs of house bricks on each corner of the cradle.

6. Preparing and Sanitising for Use

If the barrel has been newly shaved and toasted, it needs to be conditioned before I use it, starting a few days ahead.

First I wet the oak properly for a few days to expand the staves so they expand tightly against each other and develop a waterproof seal. Skipping this step could result in a leaky barrel in later steps. This is a job for outside, but preferably in the shade if it is too hot.

I put a couple of buckets of water into the barrel and stand it on one end, filling the upper end piece with water and splashing it over the edges in all directions. I repeat this every so often over a few hours.

Later I put the barrel on its side and roll it around a bit wetting all staves on the inside and then stand it on the alternate end filling the end piece, splashing down the sides again.

I repeat this over a few days leading up to when I need to use the barrel.

The final steps are done close to the time of use.

(Some winemakers omit this next step, but there is a real risk of one of the types of over-oaking, in this case with the harsh toasting products, which is very common in beginner wine-makers. Whilst an over-oaked wine may moderate over many years or by fining, it is far preferable to avoid over-oaking in the first place.)

I fill the barrel with a bucket of very hot water and roll / rotate it in every direction, even on to the ends. When pouring out and discarding the water I note the colour. This needs to be repeated with fresh hot water several, sometimes many times until the dark colour diminishes to a pale tea colour.

To sterilise I put a bucket of a strong PMS solution (see the article on sanitisation) and again ensure the entire inside of the barrel is thoroughly sanitised by rolling rotating in every direction, including both ends. This needs to be done very thoroughly, so I spend about half an hour sloshing around the PMS solution.

The PMS needs to be thoroughly rinsed away, especially if you are filling with a fermenting wine so two thorough rinses with at least a bucket of water. Keeping the water moving around each time on all sides and ends

Then the barrel can be filled with wine - either filled two-thirds if a vigorously fermenting wine, just short of full if fermentation is almost complete or in the malo- stage, then bung with an air-lock is fitted. If I'm filling with a stable wine the barrel can be filled to the top, PMS adjusted and bunged.

7. Monitoring your Wine's Development

I sample the wine at least monthly to ensure the desired level of oak influence is being achieved. If the oakiness is too great, then the wine has to be moved to another container either an old inert barrel or a glass, stainless steel or food-grade plastic container. If none of these are available then bottling may have to be considered soon.

When evaporation has left a gap in the top of the barrel (ullage) I need to top up the barrel, either from a maintenance quantity of the same wine, or from a bottle of a similar wine. There is a technique of rotating the barrel to "2 o'clock" position to achieve a tight seal around the bung and a vacuum in the evaporating ullage (no longer around the bung and able to seep air), but this requires an extremely stable wine and very sound barrel and the risk of a cork blowing and losing 100 litres of wine before discovering it seems too great a risk. Not for the faint hearted.

Between rackings the barrel should be rinsed to remove any lees or wine and then "rumbled" with a length of stainless or galvanised steel chain inside with a bucket of hot water to remove the tartrate build-up inside the barrel. Rumbling is rolling the barrel around for an extended period of time, letting the chain fall and roll on all internal surfaces, including the end to scour the surface. Repeat with a new bucket of hot water as many times as necessary to clear the dark colour (in the case of red wine barrels). Follow up with sanitisation and twice rinsing before refilling.

A common error in amateur winemaking is over-oaking by neglecting to condition the oak by soaking away the harshest of the woody and toast products before adding to the wine. (In some styles of wine these are desired or are neutralised during active fermentation, but this should be only done by trial and error on small quantities of wine or with specific instructions to achieved a particular style of wine)

Today there are a vast number of choices for wine storage / maturation vessels, so as well as storage in oak vessels, the other ways to impart oak flavour to wine are planks, staves (or sticks), chips, shavings or powder additives. The decision of which to use will depend on where and how the oak flavour is intended to be added.

Reputable suppliers can advise on dosage rates and types to achieve a particular style and suiting the quantity and format of containers you will be using.

8. Consider the Alternatives

What are the other alternatives to barrels? Eg Planks, Staves (or sticks), Chips, Shavings, or powdered additives.

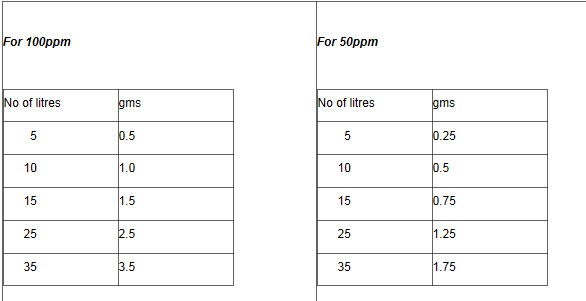

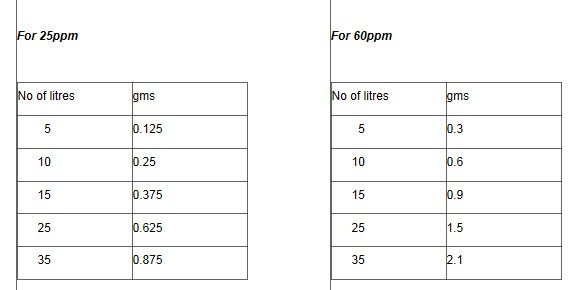

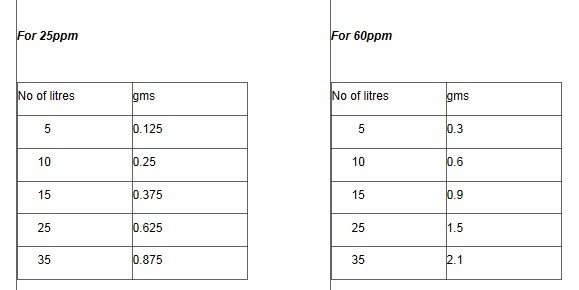

For a small vessel with a small opening, powdered additives, shavings or chips may be the only practical alternative because they may be the only oak you can physically get into the container. Typically dosage ranges for chips are 1 to 10g per litre. I have no experience with powders or shavings so I recommend the advice of a reputable supplier. Other than with powders, don't forget to soak the shavings or chips in hot or boiling water and rinse until a pale tea colour is obtained, otherwise the flavour will be too harsh. Then sanitise and twice rinse before using with wine.

For larger vessels with wide openings, staves may be practical, in addition to chips and powders. There are even staves available connected end to end in a "Z" folding manner that can be lowered into a vessel, for example a demijohn, and retrieved the same way, tied together by a food-grade plastic filament or stainless steel wire.

If you have a large vessel with a large mouth, like a stainless steel tank or a plastic drum, then oak planks can be used, either singly, or assembled in modules again tied together by plastic filament or stainless steel wire

Dosage rates may vary and suppliers should be consulted, but I have successfully used oak planks at a rate of 0.25 square metres per 100 litres with medium toast French Oak.

Again these should be soaked in boiling or hot water rinsed, sanitised and twice rinsed before using with wine.

Reputable winemaking suppliers like several of our sponsors can advise on types and dosage rates. The choices are generally French or American oak, and light, medium or high toast (and even untoasted).

If the container has a wide enough opening, oak chips can be placed in a mesh bag. Suitable food-grade nylon mesh can be obtained from winery suppliers. This is called "tea-bagging" and makes the removal of the chips much simpler.

The wine should be sampled periodically, at least monthly, and once the desired level of oak character is achieved the wine can be racked off the oak and continue maturation. If after racking further oak treatment is required, the chips can be rinsed and returned to the wine. With chips and planks it may be necessary to scrape off a tartrate build-up to continue effective oak treatment. If there is any chance of contamination during the removal process the oak should be sanitised and twice rinsed before returning it.

Rankine, B. C. (2004) Making Good Wine: A Manual of Winemaking Practice for Australia and New Zealand, Pan Macmillan Australia, Sydney.

Iland, P, Gago, P., Caillard, A. & Dry, P. (2009) A Taste of the World of Wine. Patrick Iland Wine Promotions, Adelaide

Back to top